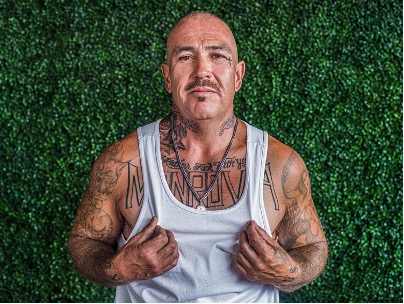

Male, Age 49

Crossed the border at 4 with family seeking economic opportunity and family reunification

US high school junior; US occupation: Manufacturing quality inspector

Issued voluntary departure at 35 after serving time for a felony.

Left behind: mother, father, 2 children

Mexican occupation: construction worker

Mexico City, Mexico

Abel I

June 2, 2019

Interviewer: Abel, you came to the States at age four?

Abel: Yes.

Interviewer: Do you have memories of the day you came to the States?

Abel: Yeah, I do. I have memories of me crossing. Drove in a station wagon with the coyote. It was me and my mom— my mom is really light-skinned, and she looks Caucasian. She put a camera on and I was in the back playing with some kid with the little cars and stuff, and just drove right across. Got to a safe house and my dad came and picked us up, and that was it. That same week, I started going to kindergarten, got enrolled in school. It was easier back then. It was in the 70s. So I started going to pre-kinder. I went to M___ Elementary School, all the way up to the fifth grade. I graduated, and went to C___ Junior High School. And then I went to M____ H__. But it was a big process. My mom and dad both had to work—going for that American dream. I am the only child, so I found my friends in the streets. So as a young kid, I started hanging out and I did become involved in the gang culture in LA.

Interviewer: You had said that your dad actually came over legally for work

Abel: [Affirmative noise].

Interviewer: And he worked with horses at the racetrack?

Abel: Santa Anita Race Track. Hollywood Park. He went back and forth to Del Mar. He was a groomer, he worked for years in the track. Eventually he left that and he started working for ACME Corporation, which later on turned into Stanley Corporation. He retired from there.

Interviewer: What did he do there?

Abel: He was a machine operator. A little bit more money than track.

Interviewer: And your mom, what’d she do?

Abel: My mom, she’s the one who got me the job at Jan-Kens Enameling. She She was in the painting department. I’m not sure, she was a racker in masking. She worked at the same place I did. She’s still working there. She’s been there since ’84. To this day—

Interviewer: Wow.

Abel: —she’s still working there. She has two more years before she retires.

Interviewer: That’s great. You were talking about driving across the border. When you got here to the states, did it seem different to you?

Abel: That I don’t remember. Well, it was different, because as a kid I lived in the city, I lived here. And Monrovia, it was a quiet town for me. It was nice, it was a pretty town. Sidewalks and everything was, you know, pavement and stuff. It was nice. Park areas. I liked it, it was a beautiful place. I lived there all my life almost, just one spot.

Interviewer: So you said that you got involved with gangs. How old were you?

Abel: I was about fourteen, fifteen, going to high school.

Interviewer: Why do you think it happened?

Abel: I think it was because I didn’t have anybody to watch me. My mom had to go to work. She got out of work, like seven. My dad took off to work at two. He didn’t get back until nighttime. So, I had this lapse of five hours that I would get off of school at 1:50 and I had a park across the street from my house that a lot of my friends now hang out at. We’re hanging out. We started off just hanging out with the skateboards and the bikes. Little by little, it led to other things. So, I started hanging out with the homies.

Interviewer: We see that a lot, a lot of the deportees that have come back talk about that.

Abel: Yeah, it kind of pulls you. That’s all you see. It was funny, because like I said, you go out there, you see a beautiful town, but you don’t know what’s there until later. Because out there, everything’s nice, compared to out here. It might be gang infested, but in the daytime it looks like Beverly Hills. You come out at night, it looks like Iraq.

Interviewer: So what about school, did you like school?

Abel: I loved school. My first years, elementary and junior high, I was in a GATE program, gifted and talented education, I was pretty smart. I did really good. When I started out hanging out with my friends, that’s what messed me up later on. And I didn’t get in trouble a lot. I mean, I’ve only been to jail three times. Except I did a lot of time for it. But I mean, I wasn’t going in and out of jail. I wasn’t going to the halls. I’ve never been to juvenile hall in my life. It wasn’t until I was an adult that I started getting in trouble. I mean, I had a little bit of run-ins, but I never did any time. I was pretty good. I was scared of my mom and dad, they whooped me [Chuckles]. So I tried to do good to please them.

Interviewer: When you started getting with the gangs, what did that mean? What kind of behavior did you guys engage in?

Abel: I don’t want to defend the gang culture, but, I mean, we weren’t messing with innocent people. I mean, it was just a bunch of kids, we hung out. Our rivalry started from high school, from the football games. That’s how our rivalry started, with the other schools and stuff. That’s how we started having, I guess, problems with other cities and stuff. But I mean, everybody talked to us. People weren’t scared of us. I mean, “Hey, how are you doing? What’s up?” “Hey, Juan.” They would talk to us. We only had problems with the people we didn’t get along with. We weren’t out there causing a ruckus. I never was involved in selling drugs. I never got busted for stealing. I never even got busted for shoplifting. I was a good kid. I just, I had that double life. I used to like to go hang out, but I always liked to work.

Interviewer: Did you start working as a kid to make money?

Abel: Yeah. I started working as a kid to dress the way I wanted to dress because my mom would tell me, “No, you can’t wear those pants. They’re too big.” Or, “You can’t wear that shirt.” Or, “No, you can’t cut your hair like that.” So for me to get what I wanted to wear, I started working at the swap meet. I used to work with these Chinese dudes selling shoes. I was thirteen, fourteen. I started making my own money selling shoes and stuff. That’s how I started buying my clothes.

Interviewer: That’s great.

Abel: Because my mom was like, “If you want to dress that way, you better buy your own clothes.”

Interviewer: Did they know that you were involved in these gangs?

Abel: I think they might’ve suspected it, but they didn’t want to believe it until later, until they finally knew it, until I was deep in it. Because they would see that I had little tattoos and stuff, but they wouldn’t … I mean, they would see my friends as the kids I grew up with. They didn’t see them as gang members. They knew them as so-and-so’s son, and so-and-so’s daughter. I mean, your mom’s always going to think you’re an angel no matter what you do.

Interviewer: Does she still?

Abel: Yeah, still to this day. I love my mom, I love my dad. They’re good. They’re good people.

Interviewer: So they were working really hard and you were just trying to make your way?

Abel: Yeah.

Interviewer: So you got married at some point?

Abel: Yeah.

Interviewer: And you got in trouble at some point?

Abel: [Affirmative noise].

Interviewer: Which happened first?

Abel: I got in trouble first. Like I said, I had already gotten my papers in ’88.

Interviewer: Talk a little bit about that, about the papers, because that’s interesting.

Abel: Okay. Well, since we were illegal, so we were scared because they were doing round-ups—I don’t know what they call it when they start deporting everybody and the buses come. I don’t what they call them…redadas. I don’t know how they say it in English.

Interviewer: Raids?

Abel: Raids, yeah. They’re doing raids. INS [Immigration and Naturalization Service] raids and stuff at certain places. And we were scared it would happen at school and stuff. My dad, he was all right, but me and my mom were like, “No, we need to fix our papers.”

Interviewer: Was he still on a working visa or not?

Abel: No, he had already gotten his permanent residency.

Interviewer: Oh, okay.

Abel: So he’s the one who helped us get our permanent residency through the Amnesty Program. So, I guess if you had been there longer than ten years, in the States, and had been working and stuff, you had to just prove with the papers that you were working, you were paying your taxes and stuff. So they gave us our green cards, my green card.

Interviewer: That’s great.

Abel: The only thing is I didn’t appreciate it, because I get it in ’88 and then 1990, I get busted for a joyride.

Interviewer: A joyride?

Abel: Joyride, yeah. Get busted joyriding—

Interviewer: So, you stole a car?

Abel: We stole a car, me and my buddy. The keys were in there, we took off. We got in trouble. I did six months for that. But I never got deported. I just showed them my green card, I got out.

Interviewer: How old were you at that point?

Abel: I was eighteen. I was eighteen-years-old. That was the first time I ever got busted, eighteen years old, joyriding. Gave me six months. I got out—

Interviewer: You were eighteen, so it wasn’t juvenile?

Abel: No. I went to LA County. I did my time in county jail. I didn’t go to prison. Then in 1992, that’s when I got busted. That’s the first time I went to the pen. I got into an altercation at a party and there were some shots fired, and I got busted. I mean, I didn’t do it, but you can’t tell how it goes. So, I got busted with the guys that were there too, and we all had to do time. I did three-and-a-half years off of that. They gave me seven years, I did three and a half. Then—

Interviewer: What was that like?

Abel: I mean, I had never done so much time. It was hard. I remember the first year went by really fast, the second year. But then after, I still had that year-and-a-half left, I was like, “Whoa.” It seems forever. It seemed forever.

Interviewer: And were you with dangerous criminals? Was it maximum security, or no?

Abel: No. It was my first time, I was in level two. It was minimum. Medium custody. We were in dorm living. But I mean, that’s where it’s at though. I think it’s more dangerous being in dorm living than it is in cell living.

Interviewer: Really?

Abel: Yeah, because cell living, they close you at nighttime and lock your door and you’re just there with your cell-y, but if you’re in dorm living, I mean, it’s 150 beds, there’s like 300 people. If something jumps off, I mean, it’s pretty wild.

Interviewer: And you were affiliated with the gang at that point?

Abel: Yeah, I was already—

Interviewer: Did that help or hurt or have any effect?

Abel: I mean, it helped. It helped because I’m from Southern California, so when you get to a certain place, people look out for each other. So if you know somebody that’s from your area, I mean, “Hey, how you doing? What do you need?” “Oh, I need some tennis shoes. I need some sandals. I need some soap,” whatever. So they looked out for you. Certain groups, people look out for you. It was safe, I just had to participate in stuff. Whenever something happened, you have to jump.

Interviewer: Three-and-a-half years is up, you get out, they’re still not after you —

Abel: That’s when the INS hold came in. I was in Chuckwalla, Chuckwalla Valley State Prison. It’s over there by Blithe, right next to Arizona. I was supposed to get out and I didn’t get out. I went to go see my counselor and I was like, “Hey, what’s up? I was supposed to get out yesterday.” She’s like, “No, you have an INS hold.” So eventually they came and picked me up. They sent me to Florence Federal Prison in Arizona, I was there a couple weeks and they asked me if I wanted to see the judge or if I wanted to sign deportation. That time I said, “I want to see the judge.” They gave me bail, which wasn’t a lot. I paid five thousand dollars for bail. I got out on bail; that’s when I got married. I married my long-time girlfriend.

Interviewer: Oh! So when did you meet her?

Abel: I met her though, well, being in trouble. I mean, I knew her family for years. I knew her for years, but when I got in trouble, she was writing me. She was writing me letters and stuff, so when I got out, I was kind of courting her already. So we started going out. She wanted to help me out so I wouldn’t get deported, so we got married. And then I had my daughter with her. We had our daughter. I still ended up getting deported though, because I missed my court date. I moved and, I never got my court date, and they came and got me at work, INS. It was the bounty hunters or the Marshalls or something—

Interviewer: Oh my.

Abel: —because I had skipped bail supposedly.

Interviewer: Oh, I see.

Abel: INS didn’t come get me. They were some bounty hunters.

Interviewer: So they let you out of jail and said, “You have to appear before a judge concerning this INS hold”?

Abel: Right.

Interviewer: And then you moved, and then—

Abel: And then I never got the letter, so they thought I skipped bail. So the bounty hunters came and got me, took me to the INS building in downtown. Once I was there, my lawyer, he told me to go ahead and just sign deportation, that he could get me my papers easier through the outs. So I listened to him, which was stupid, and I signed my voluntary deportation. And this was in ’97, something like that. So I get out. I mean, they deport me. That same day –I’m back in Mexico-I call my wife, “Come and get me. Bring my license. Bring one of your friends, or one of her boyfriends, or husband, whoever you want to bring.” I just crossed. I crossed right across. My license, U.S. citizen. Plus, my name helps, because my name’s Abel Martine, but over there you only use your first last name.

Interviewer: Oh, Abel Martin.

Abel: So they’re thinking my name’s Abel M__. And I would say it that way. I wouldn’t say Abel Martine. “What’s your name?” “Abel M__.” “Where were you born?” “Monrovia, California.” “this guy’s a white guy.”

Interviewer: That’s great. At that point, you had married her, but you hadn’t had any kids?

Abel: No, not until later on.

Interviewer: Until later on. And then were you still working in … at the enameling?

Abel: I was working there.

Interviewer: Oh, you were?

Abel: Yeah. I came back, I didn’t tell them I got deported. I just came back to work, I was using my license, everything.

Interviewer: And had you taken those courses yet?

Abel: I was already a trainee. I had already taken some courses. I was already an inspector trainee for both magnetic particle and for fluorescent penetrant inspection. I was working already on my certifications.

Interviewer: How many years was it between when you came back and you got finally deported?

Abel: Well, when I got busted or when I was out? Five years.

Interviewer: Five years?

Abel: Five years I got in trouble, and then I did time.

Interviewer: Oh, five years and then you did—

Abel: See, I got busted in 2001.

Interviewer: So, it bought you five years of—

Abel: Yeah, I was there. Five years of freedom. But like I said, I worked. I was working, I was paying my taxes. You know what’s funny is the INS told me they knew I was there. They were just waiting for me to mess up they said. They knew I was there all that time. Once I started using my social security, they knew I had already come back.

Interviewer: Well, you screwed up, unfortunately, but even if you hadn’t, probably nowadays, if they knew you were there, they would’ve come and gotten you.

Abel: Yeah, right away.

Interviewer: Regardless of whether you screwed up or not. Things have changed. [Pause] So you had these two lovely children?

Abel: Yes. One is from another marriage. From me getting in trouble, I lost my first my wife. During the five years, I got divorced.

Interviewer: Oh, you did?

Abel: Yeah. I got divorced. I met another girl, real nice girl, and I had my son with her, right before I got busted.

Interviewer: Wow.

Abel: I was already in another relationship.

Interviewer: But you keep in contact with both?

Abel: I keep in contact with both. We maintain friendship, we try to keep in touch for the kids. Well, for my daughter. She’s a real good person. We didn’t end in bad terms, so we’re good. I’m not vindictive. I know how to forget. I know how to forgive, forget. I mean, I hope they do the same with me. It’s better to get along, especially for your kids.

Interviewer: So in those five years you got divorced, found a new partner, and you had your son. How old were the kids when you had the final drunk driving—

Abel: When I got in trouble, my son wasn’t even born yet. When I got caught for evading, my wife was pregnant—or my ex, she’s not with me any more. She was pregnant. When I was in jail, my son was born. I got to see him in visits and stuff, but at first I didn’t get to see him until later on. Because at first you got to fight your case, and then you can’t see him until later on.

Interviewer: The final altercation was drunk driving, you were pulled over.

Abel: Yeah, I didn’t want to stop. I knew they were going to get me, so I’m like, “I’m gone,” took off. I probably wouldn’t have got as much time. I mean, I should’ve just stopped, but I figured I’m just going to give them a run for their money. I figured it’s just evading, what can they give me? It turned out to be a long-ass time.

Interviewer: Six years.

Abel: Yes.

Interviewer: And did both kids come and visit you?

Abel: Yeah. They used to both go visit me. Both my exes used to go see me, too. I mean, because my daughter was small, so she used to take my daughter. And my wife at the time used to go take my son. My parents used to go see me. My friends used to go see me too. I had a lot of people go see me. I mean, I wasn’t alone. It was good.

Interviewer: That’s good. Was it the same jail or a different one?

Abel: I moved around. I was in Chino, Chuckwalla, I was in Soledad, Wasco, Delano. You move around, you move around. Reception center, it’s a place where you’re settled.

Interviewer: Was it different from your first time in jail?

Abel: It was easier. It was easier, because I already knew the world. I already knew what I had to do. I already knew how to stay out of trouble, keep to myself. It was better. It was better. I went in there with a little bit more—honestly, I was kind of dumb—but more confidence, because I already knew what time it was.

Interviewer: Did you know you were going to have to go back once you got out? Back to Mexico?

Abel: What do you mean?

Interviewer: Did you know once you served your time that they were going to send you back?

Abel: Oh, I knew it. I knew it. Yeah, I already knew because I already had the INS hold. I couldn’t participate in certain programs, fire camp, because you were a risk. You were a flight risk, whatever. So I already knew I had a hold. They told me I had a hold when I got busted. I was just waiting to get out for them to shoot me back. I already knew they were going to deport me.

Interviewer: So what was your plan?

Abel: Well, my plan was I was going to be here six months and go back. My dad sent me way out here, because I could’ve stayed in TJ [Tijuana]. I mean it’s only two hours away from the house. But, I don’t know, he figured out I’ll be better off this way. You know how they have the three strikes now in Cali?

Interviewer: Yeah.

Abel: So he was scared for me, crossing the border, they could give me three strikes or whatever. So they were scared for that. That’s why they decided to send me out here to Mexico City. And I obliged, I said, “All right. I’ll go out there a couple months, maybe a year.” I’ve been here fourteen, which helped out because I have family here. There’s a lot of my family that lives here, and I’ve met a lot of people here. I mean, I’m alive. I’m all right. I’m all right. The only thing is that I never made a plan for my future, because in my mind, I always want to go back. I don’t know if they should hear me, because right here, they know they’re talking about they want to have the Mexican dream here in Mexico, the American dream here in Mexico. I want to go back. I want to go back, I’m not going to lie. If I have to be here, which I’ve been here, I’ll do what I can to be a valuable person, to help out where I live and myself and my family. But if I could go back, I would go back in a heartbeat. If they tell me, “Drop everything you have here and go.” Let’s go. I’ll leave everything. I’ll leave everything and go. I mean, I consider it my county. Even though I was involved with the gangs and stuff. But I mean, I didn’t consider myself a bad person. I love that place. I mean, I miss it. I miss it. To this day, I can’t get used to it. I can’t get used to not having a car. I can’t get used to being able to … I mean, out here is just expensive. It’s ridiculous. You got out with your family to go to McDonald’s or whatever and you’re going to waste four days of work. It’s crazy. A hamburger, a special costs 150 pesos. Say you have two kids and your wife, that’s six hundred pesos, you’re going to make that in two days. It’s just way out. And driving, I miss driving. I miss driving. I miss my family. I miss being able to go to the beach. I was half hour away from the beach. It was cool. It was good. I miss everything out there. I do miss it a lot. It’s hard to get used to it. It’s hard to get used to it. The thing is too, I mean, even relationship-wise. Out here, I’ve been through so many relationships, because they can’t get used to my way of life still. Because I’m pro-cannabis and they can’t—

Interviewer: You’re pro what?

Abel: Pro-cannabis.

Interviewer: Oh yeah?

Abel: Yeah. Out here, they see that as bad. They see it as a drug, addict or whatever. I haven’t drunk in five years. I don’t even smoke cigarettes. But because I smoke, they see you as a bad person. I don’t know. Up there, everything’s getting legal now.

Interviewer: [Laughs]. I was going to say, it’s all getting legal. It’s tough.

Abel: But how’s work out there? I mean, is there work out there really? I mean, like in California, you don’t know about California?

Interviewer: Well, I don’t live there, but is there work there? Yeah, I think so.

Abel: I have a lot of friends that are coming out this way now too. They were out there for years too—

Interviewer: They’re saying there’s no work?

Abel: Rent is expensive, there’s no work out there. I’m like, “Come on.”

Interviewer: Oh, and you lived near Pasadena, you lived in an expensive part of California. But I think there’s work. But employment rates are low throughout the States.

Abel: Is it?

Interviewer: But since the recessions of 2008, the wages haven’t gone up as much. So, people aren’t feeling …They’re still feeling poor. Poorer than they were. So you think of yourself as American, not Mexican?

Abel: Oh, yeah. I think of myself as Mexican, but I do love America. United States, because we are in America here. I always consider myself as being a Monrovian, Californian. I mean, I paid my taxes, I went to school there. I grew up there. I guess it’s not where you’re born, it’s where you were raised. I love this place though too. I do, because out here, it’s a trip. I mean, out here, you won’t go broke. If you’re a lazy person, you won’t have … there’s work everywhere out here. You can do whatever. I mean, helping a lady take her bags to the car, she’ll give you ten pesos. If you look for stuff to do here, there’s stuff to do here. Just me, I just miss my life you know? I miss my life. It’s way different, put on a CD that somebody’s going to like … then somebody’s not going to look right, “What the heck is that?” I mean, it’s just hard, especially when you live around everybody who don’t speak English. They don’t hear your stuff. I do have a couple friends though that are from out there too though, that are deported also. Because we find each other. You’ll see somebody that has tags and you’ll be like, “Hey, man. You lived out there before?” “Yeah, I lived in so-and-so. I lived in Huntington Beach,” or “I lived in Long Beach.” “Oh, is that right? Oh man, I lived in Monrovia.” Become friends. That’s why I still speak English. I mean, I don’t lose my—

Interviewer: Oh, no. You have not at all.

Abel: I try to practice it. Plus, I’m always speaking with my daughter and my son. I listen to English music, I watch movies. I go buy the movies. I’m not guilty of buying bootleg movies, that’s not right. But I go buy the movies and I make sure that I can watch them in English. I read books too, I read English books and stuff. I try to, I try to. I just read Gone with the Wind. It’s a good book, man. The Outsiders. When my daughter comes out here, she’s the one that brings me the books. She should be coming out here in, I’m thinking in August—August, September.

Interviewer: That’s great.

Abel: Yeah, my dad’s out here right now, but he’s in Jalisco. He went to stop by to see his brothers and stuff and he’s coming down here. He came to get some dental work done because it’s cheaper out here.

Interviewer: That’s what I hear. So you apparently live alone in your own apartment?

Abel: Yeah, I’ve got my own apartment.

Interviewer: And you can entertain the family when they come?

Abel: Yeah, exactly. I have a guestroom. I rent from one of my aunts. It was her son’s house, my cousin’s house, but he built his house apart, because it’s upstairs from his mom and dad’s house. So he more or less did it so they can help themselves out with the rent. So I rent it from them. I’m all right. I try to maintain positive. I try to keep myself positive. But I mean, I do miss it. I’m glad I can say this. Nobody understands me when I talk to them about it, they’re like, “Oh, you’re cool out here.” No, you don’t understand. I tell these guys here from Mexico, my friends here in Mexico, I tell them, “Imagine you lived here in Tecámac all your life and all the sudden they tell you, ‘No, you can’t be here.’ And they take you somewhere else. What would you do? How would you go about finding friends? How would you go about finding work?” I mean, it messes with you. It does. It does mess with you psychologically. It does depress you. I got out of it. It helped me stop drinking. I stopped drinking, because when you drink, I mean, that makes it worse. It makes it worse, so I thank God I stopped drinking, because I was drinking a lot. A lot. Every day, I didn’t care. But I’m better off now.

Interviewer: Yeah, if you drink, it’s hard to work too.

Abel: Yeah, you can’t. You don’t go to work. You don’t go. But I’m hoping, I’m hoping I can go back. I mean, I need to go to the U.S. embassy and check it. Sometimes everyone tells me, “I mean, you’re an ex-gang member. They’re not going to let you go back.” But I mean, you never know.

Interviewer: I think the current administration, nothing good is going to happen [Abel chuckles]. But maybe a new administration, maybe some immigration policy will be more forgiving of deportees, in at least visits.

Abel: Well, I mean, I’m thinking of working on a hardship case because my mom and dad are older. And I’m the only son. If they don’t want to come back, they’re U.S. citizens, who’s going to take care of them? We’re looking into that. Maybe I can do it that way, because they’re telling me have my kids ask for me because my daughter, she already turned twenty, she’s twenty-three. So supposedly she could ask for me to return. But that’s if you don’t have a prior record. I think I’m better off on having my mom and dad asking for me because they’re the ones who would need me to help them out, because my daughter, she’s on her own. She can do whatever. But I need to check it out.

Interviewer: Keep working on it.

Abel: I try to come (to seminars), whenever they have things like this or whenever they have the certificates, I try to take them. I’m trying to build a little curriculum of stuff to have, to show them I’m trying. I mean, I work, and I never got in trouble here. Since I’ve been here, I’ve never stepped in jail. Ever. Me getting deported just woke me up, dude. I messed my whole life up for messing around.

Interviewer: And you’ve learned this new skill in Mexico, masonry.

Abel: So I could use that out there. You get paid good being out there, being a mason. Good money. Carpentry. You learn a little bit of everything out here working.

Interviewer: It’s interesting, I’ve talked to a lot of deportees who say it’s hard to get into the construction industry, but you didn’t find it that hard? Was it connections through relatives?

Abel: No. I mean, you know what it is? I guess I had all my papers. When I first got here, I used to get taken off the bus a lot. This happened today. That’s why I was late. They had these checkpoints and they make all the men get off the bus and they search you. I don’t know if you heard about stuff like that? So they take all the men out and they check you for weapons and stuff and they let you back on the bus. It took like half hour. [Pause]. I forgot what I was saying.

Interviewer: I was asking you about your papers.

Abel: Oh, about the papers. About what?

Interviewer: Because I was saying that you got this job in construction—

Abel: Oh, how did I get it? Okay. Well, the reason I got my ID was because they were taking me off the bus and they asked me if I was an MS guy or whatever, so I went and got my ID. So I’ve had it since I’ve been here. So once you have your ID, you can get your Curp [Mexican identification code], you can get your social security number and all that. So it was easy for me to get hooked up. And then later on learning the trade, now I get my own jobs from word of mouth. So I’ll tell somebody, “Hey, I mean, if you need something done, let people know I know how to do certain type of work,” whatever. And they’re like, “All right. Give me a call right now.” Right now, I’m working at a cousin’s house, doing the driveway, pouring concrete and stuff and laying brick down. So from there, I get chances to work, from word of mouth, they call it, letting people know. Because I’ll do everything. I’ll paint, whatever I can do. Whatever I can do to make money.

Interviewer: That’s great. You’re doing really well.

Abel: Thank you. I’m trying, I’m trying. Trying to stay positive. Trying to stay grounded.

Interviewer: Well, it’s great that your family can come see you and that they do come see you, and hopefully you’ll find a way to get back.

Abel: I hope.

Interviewer: I hope so, too.

Abel: And if not, I’ll make the best of it here. I mean, that’s the thing that I always keep in mind too. I mean, it’s not always going to happen the way you want it. It’s just when I was going to get out this last time, I was praying to God that I’m going to get out, and when I get out, I’m going to do good…. God knows where he’s going to put you. I’m here.

Interviewer: Well, good luck with everything.

Abel: Thank you.

Interviewer: And thank you so much.

We spoke again with Abel in 2022

Interviewer: When you said that hardship was the first word that comes to mind when you think of Mexico, what’s so hard about Mexico and why does hardship come to mind?

Abel: Well, hardship comes to mind because as far as looking for work or getting work. I’ve never had a job that’s lasted months. So it’s always a constant battle to provide. So that’s that hardship part, because you’ll work five, six months and then you’re out of work. And whatever little money you saved up, you’re going to have to use it up until you get another job. And missing the people that miss, my mom, my dad, my kids, my homies, my friends out there, my girlfriend’s out there and stuff. Girl friends not girlfriends.

But I’m missing the lifestyle. Since I was a kid, I always worked when I was young out there and stuff. And I had my little things. I had a car. I’ve always drove. I’ve never had a car since I’ve been here. So it’s little things. I mean, just getting up early in the morning, warming up my truck, my car, listen to some music, I’m going to work, going to the drive through. I mean, it’s just little things like that, being able to go to the park, going to the beach. Out here you have to drive hours to go to the beach and stuff. I lived half an hour away from the beach when I was out there. I lived in California. Seal Beach and Santa Monica, Malibu and all that was close to my house. An hour away the longest. So you get a chance to miss LA.

There’s nothing to do out here, especially the part where I live at. I live borderline Hidalgo, State of Hidalgo. Well, and Mexico City, because it takes me around the same time to get here. I left, I came here about 11:30. So it didn’t take me that long to get here. Got here in about an hour and a half because of traffic.

But I don’t know. I just can’t never get used to none of this. I can’t get used to it. I don’t know if it’s me being negative about it, but you could only be so positive then it always gets to you. And then being lonely gets to me, being lonely and stuff. And a lot of times that I’m lonely is because I’ve lost a person because of me being the way I am. Since my plans are always to go back, they think I can’t commit because I’m always talking about, “I want to go back. I want to go back.” So they’re like, “Dude, why am I going to be with you if you’re going to leave me?” So they end up leaving me because I’m always talking about how I want to come back. “I want to go back. I want to go back.” You know?

Interviewer: I was thinking back to conversations that we had when we were just chatting over the past few months.

Abel: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Interviewer: And there was a period when you were really down. I don’t know if you remember we were chatting and you were saying that it was really hard to find a job, and you felt you got what you deserved and all this stuff. I wonder if you could talk a little bit about that?

Abel: Oh yeah. Well, because I know I got deported because I was messing up. That’s what I used to tell them when I used to go to New Comienzos. I used to trip out because all the kids were dreamers and DACA and I’m like, “Dude, they were doing good. Why would you guys want me to come over here?” But they’re like, “No, we want to hear what you’ve got to say.” So it’s like, I know I did bad, but I mean, I already changed. But this is my… You know what I’m saying? This is my bed. I have to lie in it. Because yeah, I was messing up. That’s why I got deported. And that’s why I felt like maybe I got what I deserved because I mean, I was messing up out there. Not a lot, because my last case was bogus, man. I had already been deported. I was drunk driving and I tried to get pulled over and I didn’t want to stop. So I’m already deported. I mean, I’m gung ho.

And I got broke off a lot of time for supposedly assaulting a police officer, because I hit a cop car. And they gave me assault on an officer. And that’s like, what? I mean, I didn’t try to do nothing to the officer. But that’s why I feel like that. And I mean, I got what I deserved. I know I did, but I mean, I think I already paid. I think I already paid. Doing the time I already paid. Why deport me? And the first time I got deported was bogus too, because I got out, I was on bail because I got bonded out of Florence Federal Prison. I got married and we moved. You know how I have to send the change of address and stuff?

Interviewer: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Abel: I sent the change of address. So I’m on my way to work and I get picked up by, they were bounty hunters that I had skipped bail. So they take me downtown LA to the Terminal Interviewerx, or the downtown Federal Building. And my lawyer dump trucked me. He’s like, “Dude, just sign your voluntary deportation. I’ll just fix your papers for it outside.” I’m like, “Why am I going to sign a volunteer deportation? I wanted to talk to the judge. I’m off parole now.” I even discharged my number. But my dad, I don’t know, he brainwashed my dad. My dad’s like, “Nah, you’re going to make me lose the house.” And not knowing I’m like, “All right.” I signed away my… I should have went and talked to the judge. So I got deported. I get to TJ, I’m back the next day. So I was out there just living it up.

Interviewer: Why has it been so hard though here to find a fresh start, to land on your feet, to get this second chance? Why has it been so hard here to make things work?

Abel: Oh, I think it’s hard for everybody. I think it’s hard for everybody. There’s no work. I mean, there’s not a lot of work. And I think it’s hard for me because at first, they don’t really want to hire you because they think you’re lazy, a druggie or something because of tax and stuff. They don’t want to hire you, until they give you a chance. And another thing is hard is because a lot of the work is out here. When I do work and I get paid good money, I have to leave the bed and come work into the city. So for me to get to work here at eight o’clock in the morning, I have to leave 5:30 in the morning because of traffic. I get out at six o’clock, I’ll be home at nine o’clock at night. So do you really want to do that? So you might be out there not getting a lot of money and work out that way.

It’s hard to work though, because there’s not a lot of companies that are hiring, especially after the pandemic. It’s been hard. It’s been hard. I think that’s why a lot of people got stressed out being home all the time and not having no cash. I think it’s just hard overall just for everybody, even other than deportees. I think we have it harder though, because of the stereotype of us being gang members and they still see us that way. I don’t know. I even let my hair grow out. I don’t know if you noticed, but back then I was always bald head and I keep the same clothes. It’s like, you can’t lose that style. That’s the way I grew up at, you know what I mean?

And that’s another thing out here and they look at you like, “Dude, you’re old and you still dress that way?” I mean, if you only knew that’s how we always, everybody dresses that way, my friends. I don’t know if it could be called a culture. I don’t know. It’s culture. That’s the way I grew up, and the Chicano culture. So that’s why I dress the way I dress. I hear they look at it funny.

Interviewer: So it’s both that you want to keep parts of your identity, right?

Abel: Right.

Interviewer: And it’s hard because you’re stereotyped for it.

Abel: Yeah, yeah. Yeah, because I mean, they have to see me the way I am. That’s the way I see it. But I know I have to go through the looks and stuff. But yeah, I’m me. Why should I change for these fools? I don’t think I have to so, and I don’t. I don’t. I don’t care what they do. I mean, it doesn’t affect me. I try not to let it affect me. It doesn’t affect me, like if somebody tries to put me down, I’m not going to let it get me down. It might get me down later when I’m home and I think about it, like damn, he ain’t right. But I mean, I try to just let it go.

Interviewer 2: So it seems like it might be more of a problem than the type of the work you do, because it’s like you do a job. You’re saying, “No job ever goes on for very long.”

Abel: Right.

Interviewer 2: So it ends. And then you have to go through the whole process of finding a job, talking to people, someone trusting you?

Abel: Yeah. I think that you hit it right on the dot, work in construction and finishing something up, because usually when we work construction on our own, we work at a house. And exactly, once we finish whatever we’re going to do at that house or whatever, it’s done and you have to go look for a job again. So it’s starting over every time, every time. And maybe that’s what I need to do is find somewhere that I could work, like a company or anything, but that’s the thing about telling you about the age. I’m going to be 50. Nobody’s going to hire me when I’m 50. I could be strong, whatever. They’re not going to hire you. They don’t care. They’re like, “Dude, I’m going to have to retire you in 10 years, 15 years. Nah, man, I ain’t doing that.” They’d rather hire a kid. They’re going to have them working there for years.

So out here, the age matters a lot out here. Anywhere you go, and tattoos. They still discriminate for tats out here. You can’t. I can’t work at bean bowl. I can’t work at Coca-Cola. None of that stuff. They’re not going to hire you. And that’s the thing I say about lying in your bed. You know how I said, “Make your bed and lie in it.” I mean, you have to accept that’s the way it is. I mean, I maybe don’t have to go down there. I’m always in a constant battle with that. Yeah.

Interviewer: You said that maybe if you have to stay, you’re going to try and figure out a way to get to a call center. Do call centers not, I mean, I know they don’t discriminate for tattoos, but is there age discrimination there?

Abel: No. No. I think it’s just not knowing the computer skills, because I’ve met people that work there and they tell me, “Nah, I’ll hook you up, dude.” You know what I mean? That school, I think it’s called Bilingual Jobs in Mexico, something like that. The guy, he always calls me up, “Hey dude, what’s up? How you been? What’s up? How’s it going?” I’m like, “Hey, man.” And he is like, “Hey, did you take that computer class? Just take a basic computer class.” And he’s always telling me to do it. I’m like, “Nah, dude, I haven’t had time.”

Yeah. But it’s for the computer skills because at the call centers, they can’t see you. So they won’t discriminate you, because right there by the Bellas Artes, there’s this place where Tel Vista is. I mean, them guys are more tatted than me. I mean, big time, everywhere. You know what I mean? And they still work there, as long as they have good English. Yeah. So it’s not the tats thing. They won’t be discriminate there. I think it’s just not knowing computer skills.

Interviewer: But that would be an age thing too, right? Because young people have such amazing computer skills. You know what I mean? I’m like you.

Abel: Yeah. Yeah. I mean, I didn’t have a cell phone too when I got into Mexico. Back then I’d wear the beepers, 911 I’d have to call.

Interviewer: Yeah.

Abel: Yeah. Because I mean, I didn’t have a phone until I got here, a cell phone. So yeah. And we didn’t grow up with that. I grew up playing on the bikes outside and freeze tag and tether ball and running around. And I lived close to the canyon, so I would go fishing and we used to go swimming in the canyons. And I grew up being in the dirt and stuff. And now I’m all hooked on the phone and stuff, because you get to it, you get hooked on it. But I use it a lot to see my friends out there. I look for that, see what they’re doing and stuff, and my kids.

So in a way, social media is a curse and it’s a blessing, because like I say, it gets me sad. But then another way, I mean, if it wasn’t for social media, I wouldn’t have ever knew about New Comienzos. I would’ve never known about where my friends were and stuff. Because of Facebook, I keep in touch with, I’ll say about 80% of my friends from out there, because I had lost contact with them, especially because we didn’t have cell phones back then. So it was just the house number. And since people were moving out and stuff, I mean, there was no way to get in touch with them. But yeah, social media, it’s helped. It’s helped.

Interviewer: So that’s the blessing of social media.

Abel: Of social media.

Interviewer: What’s the curse of social media?

Abel: Seeing what I’m missing. Seeing what I’m missing out there. I’ve seen friends have posted pictures in front of my old house and, “Look, by your pad.” And I’m like, “Oh man.” Seeing my daughter’s graduation or seeing her doing stuff with her friends. And instead of me being there, it’s the step-dad. And I’m like, “Dude, dang.” My mom and dad 50th wedding anniversary just happened. I was out here. Things like that. And what worries me a lot is that they’re getting older. And I’ve been able to take care of them. I lived downstairs from my uncles, I mean upstairs from my uncles. And they’re older and they have the colostomy bags and stuff. And they just have two sons taking care of them. And I see how they struggle and I’m like, dang. I can imagine my mom and dad, because I’m the only child. And at least they have people taking care, their kids come and take care of them, but what’s going to happen to my mom and dad when they’re older and they have to be taken care of? So that worries me a lot.

Interviewer: So have you thought about, I know you said you were hoping that you can get a pardon and go back, have they thought about trying to sponsor you to try and get you back, so that if they need you?

Abel: My mom and dad have been to see lawyers and stuff and they tell them, “Just wait. Just wait.” Because I had to have, I think it’s 20 years or something. I have to see how… When I first got deported, it wasn’t like now. Now they receive you at the border. And when I first got deported on the bus, the people that were getting deported that had already got deported said, “Hey man, you rip all your papers, dude. Because if the chotas gets you, if the cops get you out there, they’re going to be messing with you, man.”

So whatever paper I had from the joint and from the immigration, from INS and stuff, you get out, you rip all your papers up. And you walk across if you’re just going, go partying in TJ. Yeah. Yeah. It wasn’t like now. I mean, now they help them. Now I think they even give them a flight out here if you’re from out here. So that’s good, because thankfully I had my people there, but I’ve seen a lot of people that stay at the border and it’s pretty sad. And most of them get strung out, and they get all tweaked out and stuff. Yeah.

Interviewer: It’s bad.

Abel: The border is bad. It’s bad.

Interviewer: So what would it take to make you feel more comfortable here?

Abel: Man. I think maybe stable work. Stable work and knowing what’s going to happen, knowing if I’m really going to be able to go back. Knowing if I’m going to be able to go back, so I could quit chasing the US dream and maybe make me a Mexico dream. You know what I mean? Because I’m always thinking I’m going to go back, I’m hopefully whenever. I would like to know if I am, if I can go back. That would help out, because I’m uncertain what’s going to happen because I can’t make plans what I’m going to do with my life, because I’m pulling that way. I want to go that way. But what if they tell me no? So I would want to know what’s going to happen, so I could… Maybe it’s an excuse. I should start just making a life here. It’s that Gemini in me. I’m iffy. I don’t know what to do.

Interviewer: So is the waiting, were you given a certain number of years before you could apply for a visa?

Abel: I’m not sure if it was 15 or 20 years, because I already had my papers. So I mean, my IMS number is my file. When I went to the immigration, my green card number is my inmate number for the feds, for the immigration, because the feds are just immigration too. Yeah. So I had my green card and I don’t know if I lost it completely, because I voluntarily signed my deportation. So I don’t know if I have a chance.

Interviewer: So did your parents see you in the New York Times?

Abel: Yeah.

Interviewer: What’d they think?

Abel: Oh, they were happy. They were glad. My daughter, a lot of my friends. I shared it on Facebook and stuff.

Interviewer: You did?

Abel: Yeah. And they were like, they were thumbs up. Yeah. A lot of my friends were really happy. Yeah. I don’t know. They care about me. A lot of my people care about me. They want me to do good. So thanks. Yeah.

Interviewer 2: So talking about steady employment, it seems like currently your construction is not and there’s constant finding new people to accept you and hire you, and it’s hard. But you’re saying that maybe call centers are better. What is it, is it the time that you from learning the computer, or do you need to buy a computer and you don’t have the money to buy one? What is it?

Abel: I think it’s the time, because I say we work Monday through Saturday here in Mexico.

Interviewer 2: Yeah.

Abel: And I’ve looked for this place called Rya. It’s called la Red de Innovación para Adultos. So it’s adult school in other words. And they give you classes that are really cheap, computer classes and stuff, but they’re 4:30 to 6:30 in the afternoon on weekdays. I don’t get off of work until six. And Saturdays it’s eight to 12:30.

Interviewer 2: And you work on-

Abel: I work Saturday. So the only way I could do it is if I were out here to call semana inglesa English week. I don’t know. That just means Monday through Friday, semana inglesa.

Interviewer: Yeah. Yeah.

Abel: Nobody’s going to hire you Monday through Friday. So I’m thinking maybe, I don’t know. I remember back in the days there was a typing tutor and…

Interviewer: Yeah.

Abel: I just have to make time. I think I have to find a way to make time.

Interviewer: Do you have a computer?

Abel: No, I don’t have a computer. No, no.

Interviewer: But I think in those jobs, they give you a computer.

Abel: Yeah.

Interviewer: Because you have all the other skills. I mean, you could talk to people easily. You’re smart. I remember you said you were in the gifted program when you were-

Abel: Yeah. When I was young.

Interviewer: And you have the skills, the social skills, the cultural skills to deal with people in the US. So you have all that. It’s just a computer.

Abel: Yeah.

Interviewer: And I mean, as you go forward, I don’t know. I mean, hopefully you’ll be able to get that. But in the meantime, it must be tough having a new job every few months.

Abel: Yeah. Every few months.

Interviewer: And you feel like someone’s going to look at me again, and they’re going to think I’m too old and-

Abel: Yeah. Yeah.

Interviewer: It’s tough.

Abel: It’s constant. Yeah. It’s a constant battle. It’s constant mental… I don’t know. You’ve got to be strong minded. You have to be strong minded.

Interviewer: Has anything gotten better since I saw you last, let’s say, or since you came?

Abel: Well, I mean, I have to look… Yeah. Everything’s getting better. Not better money wise, I mean, just I guess my outlook on things. Like I said, I’ve stopped drinking faster. Before I would drink for a long time and I’ll let it get to me and stuff, and I’ll be drinking for a year. You know what I mean? And now I’ve noticed that once I started doing bad, I’ll notice, dude, remember you were fighting with your friends and stuff? That’s not good. Or I wasted my money. I waste my money out here. You know what I mean? You don’t make enough money here. And then you’re over here partying, going to bars and stuff. It’s not cool.

But I mean, good things, man, it’s just having my family still around. That to me is good. It’s good. My dad, I mean, my dad’s 76 years old. I mean, it’s not old, you know what I mean? He’s still up, but he comes on the bus. He doesn’t want to fly. My dad came on the bus from LA.

Interviewer: Oh gosh.

Abel: To see me. So I’m like, that’s something awesome. I’m like, “Dude.” I mean, I’m like, “Damn.” My dad’s good. He is a good dude. You know what I mean? To come on the bus to see your son.

Interviewer: That’s good.

Abel: It’s three days, two nights, something like that. Yeah. He came Thursday around midday. He didn’t get here until Saturday in the morning.

Interviewer: Wow.

Abel: And he’s going to be out here for my birthday too. So that’s going to be cool to have him for my birthday.

Interviewer: How long does he stay when he comes?

Abel: He stays for a while. My dad stays for a while. He stays for a month or two. My mom, when she comes, she only stays two weeks.

Interviewer: Wow.

Abel: Because she has to go back. My daughter has to go back to work and stuff. But my dad, he’s here for a while. He’s retired. He’s good. He gets his money out here. It’s a lot of money. He gets $2,000 a month out there. And out here it’s 40,000 pesos.

Interviewer: That’s pretty far.

Abel: So yeah. So it’s good, good money. He takes me to Burger King and McDonald’s, Carl’s Jr., places I never eat. Because I mean, you can’t just go eat at a fast food restaurant here if you’re not really making that much money. That’s maybe once a week or something if you want to. But he treats me, he spoils me. He spoils me. If I need stuff, clothes, whatever, he stocks up the fridge. He’s like, “Dude, you’ve got to buy toilet paper.” And he buys salt, buys me everything I need. Brings me my care package.

Interviewer: Yeah.

Abel: He hooks me up, hooks me up. And plus, I get to see him. But I do see he’s getting older. Every time he comes, it’s getting hard for him. It’s getting harder for him.

Interviewer: I can imagine.

Abel: Yeah. So maybe another thing, another plan of mine is if I can go back is living closer to the border, living in TJ, because I tried living out there for a couple months.

Interviewer: It’s really close.

Abel: Yeah. It’s real close. It’s real close. And out there, there’s work out there. It’s easy working out there.

Interviewer: Yeah.

Abel: It’s just the hustle. It’s busy like out here at TJ. Same thing, man. [00:23:00] There’s traffic. There’s hustle. There’s-

Interviewer: Yeah.

Abel: And there’s a gang of people out there too. There’s a lot of people.

Interviewer: And here you have relatives.

Abel: Family.

Interviewer: And you have an inexpensive living situation.

Abel: Yeah. I’m more or less stable where I’m at.

Abel: And to go back out there, when I went out there this time, because the last time out there was in 2019 before the pandemic. I was planning on staying out there, but then I started thinking about it. Dude, I don’t have a bed. Out here I have a bed. I have a fridge. I have [micro 00:23:29]. I have a TV. [00:23:30] I have my gym. I have my house, couches. I mean, I have a house.

Interviewer: Yeah.

Abel: And to start over again, it’s like, dude, it took me all these years to bank what I have. Well, how long is it going to take me to have all this again?

Interviewer: Yeah.

Abel: Because my friends are like, “Ah, don’t trip. I’ll take you a couch. I’ll take you a TV,” But I don’t want to be imposing on people either.

Interviewer: Right.

Abel: They have their lives now too.

Interviewer: And your daughter, what’s she doing in the US now? How old-

Abel: My daughter is 26. She’s 26 years old.

Interviewer: Not bad. Yeah.

Abel: Yeah. She’s going to college. She wants to be a teacher.

Interviewer: Nice.

Abel: Yeah. But she’s been off and on going to school, because I don’t know. She starts studying. She stops for a while. But her plan is to be a teacher. Right now she’s working at, I don’t know what it’s called. It’s some juice place, but she does pretty good. She’s a manager there. She’s doing all right. Yeah.

Interviewer: Is she married?

Abel: Single. She’s single. Yeah. No kids.

Interviewer: That’s really good for now, right?

Abel: Yeah. She’s trying to finish her school and stuff and-

Interviewer: That’s great.

Abel: She just got a car out the lot. She’s paying her car payments and stuff. So she’s like, she doesn’t want to get married right now.

Interviewer: If you had any advice to give someone who was coming over the border, just back to Mexico, a situation like yours, deported or whatever, what advice would you give them?

Abel: I would tell them to get their papers right away.

Interviewer: Yeah.

Abel: And use your English. Use their English to their advantage, because I didn’t take advantage of that. Because if I would’ve started working in call centers when I first got here, I think I would’ve been good right now. I would’ve learned computer skills by now. So I think I would tell them that, to use their English to an advantage. Because I didn’t take it serious, being deported when I first got here. I think I partied. To [00:25:30] me, it was like when I first got here, it was fine. I’m like, dang, I’m out here. I was just drinking, partying, you know what I mean? Then later on it was like, whoa, wait a minute. I’m stuck. I’m stuck. I’m stuck. Yeah. But I would tell them that, just to use their English to an advantage. Try to get a job with social security, so they can have medical insurance, medical benefits and stuff, because it’s hard when you have to pay it on your own.

And maybe [00:26:00] get some type of, I don’t know, psychiatric help or psychological help, you know what I mean? So you won’t be so down. Or talk to somebody that’s been through that, so they won’t be gung ho out here. Be careful out there with the cops too, because the cops are punks out here. You know what I mean? Yeah.

Interviewer: I like when you just say, “Hey, how are you doing?”

Abel: Well, I appreciate you guys. I know you guys truly care for us, [00:27:00] me and everybody out here. You guys are really worried. I mean, and I think sometimes that you guys wish you could do more or-

Interviewer: Yeah.

Abel: But I know it’s hard. It’s hard. You can’t, you know what I mean? It’s hard, and it’s hard to get financial help and stuff. And I’m pretty sure you guys are out here probably using your own money coming out here.

Interviewer: I mean, I don’t know. As you said, advice you were giving-

Abel: I wish I could give advice to the kids out there that haven’t got deported yet. Take care of your papers. That’s one thing my dad used to tell me when we first got the amnesty papers, but I was already messing up. I was already starting to be running out with little gangs and stuff. And he was telling me, “Take care of your papers, dude. Take care of your papers, man.” And I used to think nothing of it, because before you used to go to jail and get out. They didn’t deport you. As long as you showed your green card, you’d be out.

Interviewer: Yeah. Yeah.

Abel: And all of a sudden, man, I was like, “What?” Yeah. Yeah. But I would tell them that. Take care of your papers and watch who you hang out with, and don’t do stuff you don’t want people to do to you. You know what I mean? Just be cool out there. Stay out of trouble, because you miss a lot. You know what I mean? Especially being in the gangs and stuff, you know what I mean? [00:28:30] At the end of the day, the people who you were fighting in the gangs on the streets, when you go to jail, you have to hang out with them because you’re from the same area. So it’s like, what was I fighting this guy for? And now we’re all from Southern California. We’re all [foreign language 00:28:44]. We all run under the same banner and of the streets we’re fighting. And it’s like, and now I’ve got to be his buddy. It’s like, what a waste of time. I wasted years doing that.

I don’t know if you’ve talked to any people that were gangs. They’ll tell you the same thing.

Interviewer: Yeah, yeah.

Abel: When you’re in the streets, you’re fighting your neighbors, [00:29:00] you’re fighting people in another city. You go to jail and you have to hang out with this dude, because we’re from the same area. We’re from Southern California. So now we can’t fight each other. So it’s like, wow. We should have never been fighting. Yeah.

Interviewer: Yeah.

Abel: It sucks.

Interviewer: Well, anything else you want to say before we finish up?

Abel: Yeah, want to-

Interviewer: And we’re hoping, we can’t guarantee anything because we don’t control things, but we’re hoping maybe to do another piece for the New York Times. And if so, we’re hoping that we might be able to include you. But again, it’s the New York Times that will decide what they want to do.

Abel: Okay. Yeah.

Interviewer: But we’re certainly going to try.

Abel: Okay. Yeah. I wouldn’t mind even writing my own book. That would be something.

Interviewer 2: That’s cool.

Interviewer: You could write a biography.

Abel: Yeah. I mean, I’ve got so many stories, man. That would be fun. All right.

Interviewer: That’d be very cool. Well, thank you. Thank you so much.

Abel: You’re very welcome.